Building a strategy is complex -- strategy professionals dedicate their entire lives on learning and building strategies. Similarly, with every product management opportunity, we continue to learn how product strategies get influenced by new tech and innovations.

The strategy gurus like Michael Porter highlighted the fact that strategy is a relatively new field. So is software product management, which has been around for less than 50 years. The two combined presents fairly interesting challenges to the product managers/leaders (PM). Whether one defines a new product strategy from a blank slate or refines an existing strategy, a PM owns the product strategy. In the highly competitive and fast moving tech or digitally enabled industries, companies with an integrated product strategy are likely to win in the market.

We have discussed and led product teams for several years and realized that more than 80% of teams continue to have the following pitfalls:

- Product or corporate vision is not strategy: Vision is a component of strategy but doesn’t provide the choices a PM must recommend and the organization must make.

- Roadmap is not strategy: A well-aligned roadmap within an organization is definitely a key component on how the product strategy will be executed but is not the product strategy.

- Best practices or Agile is not strategy: Following the best methodologies and practices are important to be successful during execution but are not strategy.

“Strategy is an explicit set of choices made — to do something and to not do some other things”

As recommended by Lafley and Martin in their strategy book,

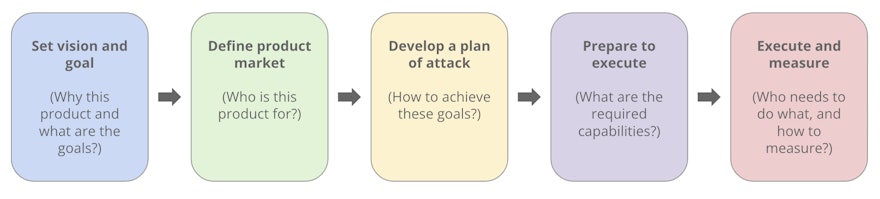

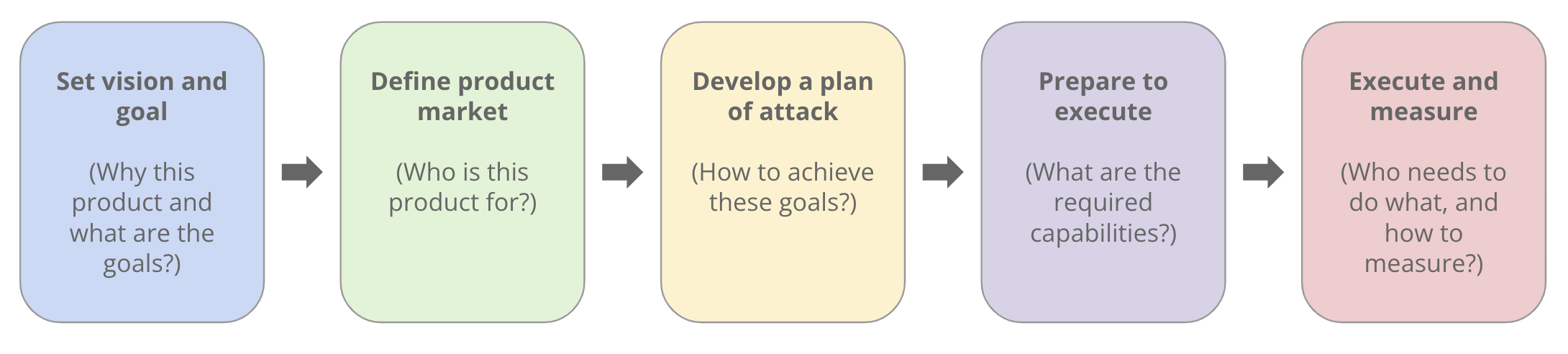

Playing to Wina successful product strategy has the following five components:

1. Product Vision & Goal

The first step is to establish a product vision and a few explicit goals. One of the most popular templates for product vision statement has too much information in it. We recommend PMs to leverage this template as a final output of, instead of input to, their product strategy:

I would recommend a simpler vision statement and a few specific goals that are inspiring for the teams and the organization. Here is an example from one of my previous experiences on the martech products:

Vision

Create a social media marketing platform that delivers unmatched results for performance marketers

Goals

(a) Establish industry leading social media marketing performance standards

(b) Achieve net grow of 300 new enterprise customers in 3 years

(c) Expand from the agency buyers to marketing buyers

A strong and clear product vision that fits well with the overall corporate vision (if different or broader) inspires people when they can relate to it. Some people may feel uncomfortable with high level and somewhat vague words like “unmatched results”. The specificity of the goals helps address some of those concerns. If a portfolio of 500 enterprise customers (200 existing + 300 new) doesn’t make the company a market leader, then I would update the goal to 1000 or 2000 customers or a number that it does.

In the early years of social media marketing, there were no widely accepted “performance marketing” standards. So we created “performance marketing” standards so that our customers can easily compare performance and we can demonstrate that we delivered unmatched results.

2. Define Product-Market

Definition of the product market consists of the type of customers, geographies, behaviors, etc. The PM thought leaders’ recommendation of “problem space” falls in this component of the strategy.

From the previous example on the ad tech products: In order to find 300+ new customers, we focused on the markets that were large enough. At the time we had 150 customers in the US. Typically, Global 1000 brands were investing the most in social media marketing. After testing the Asia market for a few months, we narrowed down our choices to focus only on North America — US and Canada. Then later expand into the UK. This meant we would have to target companies that are not listed as Fortune 500 in North America. As we continued to expand the target market in NA, we used additional demographic parameters such as, “size of social media budget”, “interested in audience insights”, etc.

The definition of the target market was relatively easier to define with demographic variables. In order to define the target market well enough, the behavioral aspect of “cares about performance” became a critical part of our target market discussions. Many relatively smaller consumer companies had started using “zero-based budgeting” and marketing ROI as their primary marketing decision tactics. As we continued to dig deeper with such behavioral parameters, which were harder than staying at the demographic level, we started seeing more differentiation from the competitors. Eventually, the target product market definition led us to make specific strategy choices.

During the definition of the product-market fit, the choices made and communicated lay the foundation for the PMs to focus on the research efforts as part of the execution. In the previous example, when the PM researched on users that “care about performance”, they asked questions, which supported our strategy or not, such as:

- Why do they care about performance?

- How do they define performance?

- Are they using traditional performance standards or they need new ones?

3. Develop a plan of attack

A potential plan of attack requires thinking on how the product goals and target product market could be achieved. This includes factors that affect product decisions (what to build first), differentiation (how is the product different), positioning (what type of messaging), pricing (how much should we charge), go-to market plan (how do we sell), measurement & analytics (how do we measure), etc. Additional decisions that fall in this section are — consideration on build-buy-partner and new product roadmaps targeting the desired target market.

In the ad tech product example above — in order to provide credible performance standards, we decided to analyze at least 10 Billion impressions for direct to consumer ads for performance. This meant we needed to build and sell the product for “direct to consumer” type marketing before anything else. This became one of our MVPs. We also needed a certain minimum number of customers to serve 10 Billion impressions and analyze the performance data. Hence, sales and marketing teams could also map their strategies and goals to the number of customers required.

In a different example, we were developing a potential plan of attack for an AI-based, predictive marketing analytics product. The target market consists of the users who deliver “digital engagement” as part of their job. I hypothesized that these users should view a product analytics dashboard, ideally on our product, at least once a day to be successful. It could be a user delight feature (Kano model). We worked with our sales team to update the talk track, as part of their strategy, to include the “predictive analytics for daily insights” as a key differentiator. As additional components in the plan of attack, we considered the pros and cons of free trials vs. entry-level pricing. We decided to offer free trials (SaaS industry standard) and continued the “test-and-learn” process. A few weeks later, the user satisfaction data turned out to be of higher quality from customers who paid a low $50 monthly subscription as compared to customers who were on free trial. This insight helped us to improve our strategy empirically-we killed free trials and signed up 100+ customers in our target segments in less than 3 months.

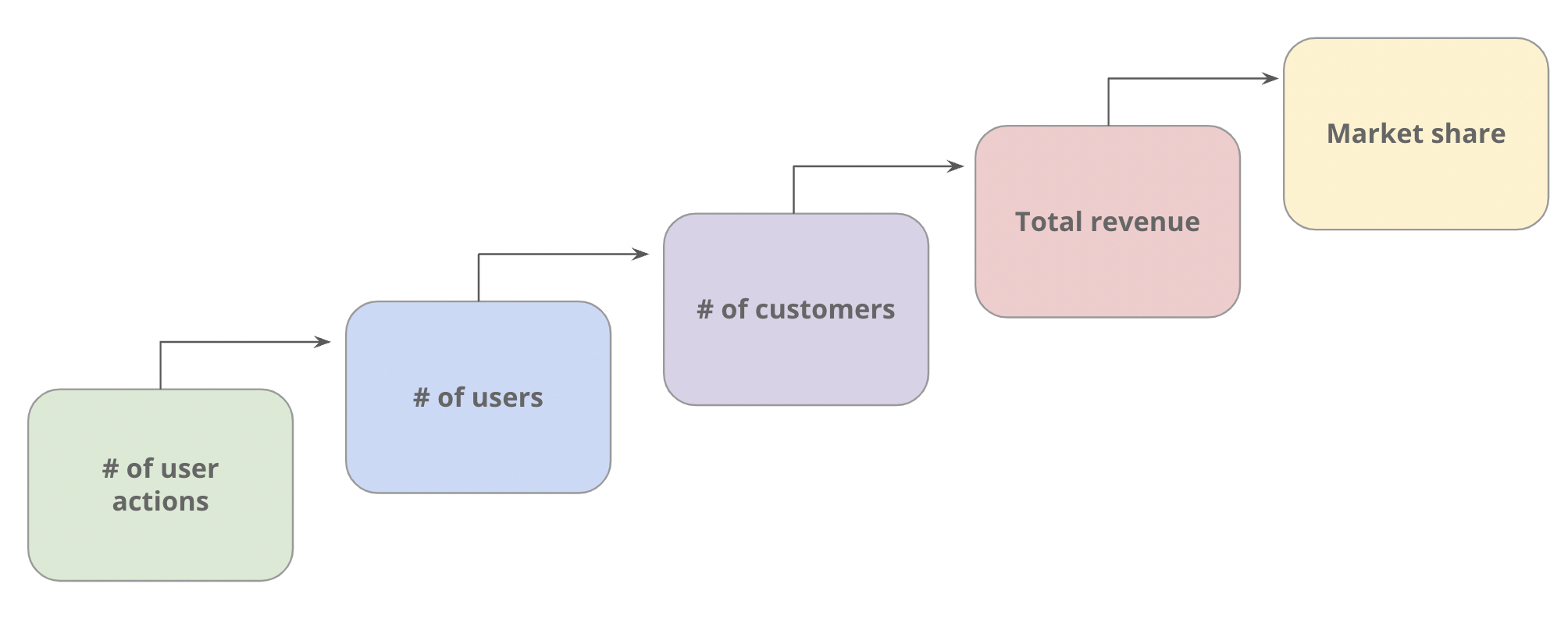

In the above example, we had the hypothesis that the growth in # of users actions (like, daily views of the analysis) would mean users find the product valuable. Hence, the plan of action informed the specific strategies to customer success and sales leads. We believed that an increase in # of user actions will drive more users to the product and eventually build a momentum. It looked like a simple model as shown below. The first three components in the plan of attack supported product goals (revenue) and company vision (market share).

The plan of attack is the key component of a product strategy where differentiation is established. Clear differentiation is not always easy or even possible at a given point of time. In today’s mar-tech industry, that seems to be a common problem. As an example of differentiation — as the head of product, I proposed several possible options for a plan of attack for large enterprise customers. My CEO, CTO and I spent significant effort evaluating at target market (user types), their potential challenges and ways to deliver a differentiated solution. Based on the available market intel and customer feedback, we couldn’t find enough differentiation against some of the largest well-known tech companies. Eventually, we decided to look at other options for our plan of attack. The CEO later decided to deal with the large enterprise customers at a higher level corporate strategy. We created a different business segment that needed its own business economics, products, and go to market.

4. Prepare to execute

In this step, a PM must understand the core strengths of the organization, market differentiators, access to customers and channels, R&D capabilities, partnerships, etc. If your organization lacks experience in acquiring and integrating a product or a team, “buy” option will be largely unavailable (that is, very risky) towards the buy-build-partner decisions. If a product roadmap needs specific data partnerships, hiring one or two partnership managers could be a part of “prepare to execute.”

In a recent experience, I led teams that did not have an in-depth understanding of the target market, and hence customer research became a key task. I evaluated organization’s in-house research capabilities and the third-party support required to quickly launch targeted research activities within the target market.

Whether it is a 1-person startup or a large complex organization with 1000s of employees, identifying and leveraging core strengths must be part of the “prepare to execute”. When I joined a startup (marketing analytics example above) as a co-founder, my other co-founder has the core strengths in product development, go to market and startup business operations. I brought my core strengths of long-term strategy, product market scaling, and innovation. As a team, we prepared to execute with our combined strengths. In the challenging marketing analytics industry, we were losing differentiation and the company value was at risk. Leveraging our combined strengths, we came up with a strategy to save the company value. I envisioned a new differentiated product, raised funding and hired a new R&D team. My cofounder launched the product and acquired 100 new customers in 3 months. As we integrated the strategies, we agreed on the growth option through M&A with an organization with access to certain type of data.

In another example, I developed a product strategy of launching a new “low-price”, potentially freemium” SaaS products. Although, the organization had historically sold only high-price products through direct sales teams, that is, we had a high customer acquisition cost (CAC). As we prepared to execute, I included creating an indirect sales team targeting a low CAC as part of the plan. Building a new inside sales team was a new capability for the organization. It would have been a mistake to overlook the lack of the required capability and to assume that the existing sales teams would have achieved the goal.

5. Execute and measure

The final component of the strategy is to identify the highest priorities, execute on them and measure for improvements & success of the strategy. This is where the popular frameworks like OKRs (Objectives & Key Results) apply or OGSM (P&G’s framework — we leveraged it working directly with my board chairman, an ex-P&G executive, in the past). The key is to focus on what matters the most.

We all understand that collaboration across teams in engineering, sales, marketing, etc. is critical for success. Collaboration works best when the functional strategies are aligned and when the times comes to execute, each function can execute with a specific set of activities and capabilities to support the product strategy and goals. New capabilities, as identified in the “prepare to execute” component, may need additional time and budget — all of which has to be factored in the execution plan.

Agile methodology has been a best practice for years for product roadmap executions. Most importantly, the strategy is not set in stone but requires the disciplined of making explicit choices, executing them and measuring progress towards the goals. Agile provides the right framework to achieve that. Test and learn process is not a new thing for a PM. It does require a bit of forward planning to ensure that a process is created to access the desired data for measurement. The PM must also understand the limitations and biases of the data.

Developing, communicating and leading with the right metrics and insights are an integral part of successful execution. I would ask every PM on my team to publish a product dashboard for their product. Depending on the nature of business and product, the dashboard may be different but at a high level the most useful themes in the dashboard are:

- Business metrics (ARR/MRR, Customer Satisfaction)

- Product metrics (# of customers/users, product usage rate, retention rate)

- Research/Insights: User research briefs/insights, Competitive insights

There are several signals when the required components of a strategy don’t exist in a team or are not integrated well in an organization:

- People tend to work very hard without achieving the desired outcomes

- Product launches get delayed

- Post product launch, there is not much love for the product in the market

For example, I come across such an interesting situation more than once in my career. Out of about 100 of customers with over $10M in ARR, none were ready to give a testimonial on the value of our products. Clearly, we lacked or lost the product-market fit.

On the other hand, one of the most interesting things about strategy is that when it works, it seems very obvious. Some of the most popular examples on the Internet, such as, initial strategy of Uber or Airbnb, are somewhat obvious strategies with the benefit of the hindsight. But if one were to ask the people who went through the years of uncertainty and doubt, it would have been probably one of the hardest things to achieve. For example, in the case of Uber, a number of decisions were made, refined and scaled over the years: which markets to enter first, how to price a ride, how to compete with new types of competitors like, Via (shared rides), etc. In part 2, I would highlight ways on how to apply the strategic approach on a regular basis.